Deep-Sea Mining and the Geopolitics of Troubled Waters

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN affiliate organization, has rekindled interest in a developing field of geopolitical rivalry after deciding to accept applications for deep-sea mining this July. Deep-sea mining is on the rise due to the global demand for “battery metals,” which are necessary to meet the complex supply chain requirements for companies that make electric vehicles (EVs) and clean energy infrastructure, despite concerns about the lack of scientific research and the potential environmental impact. Deep-sea mining has been linked to lucrative deposits of cobalt, nickel, manganese, and Rare Earth Elements (REEs), with China, Russia, and Norway representing some of the industry’s most eager participants.

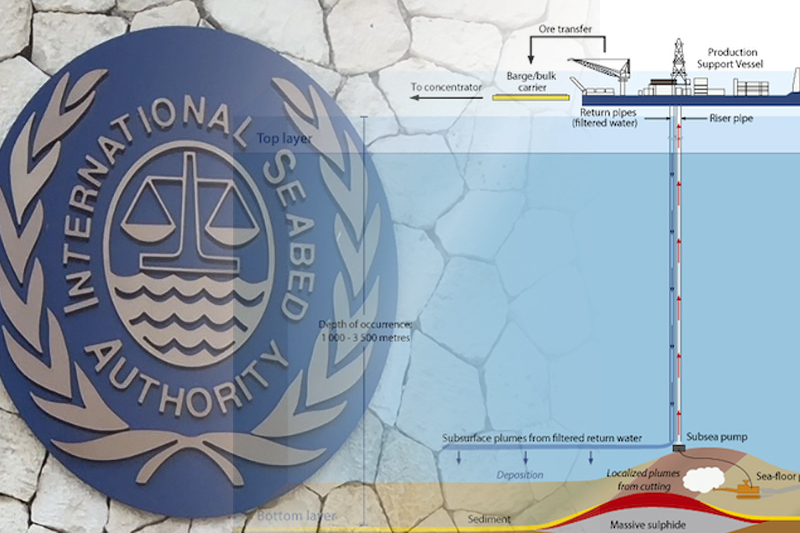

The process of removing minerals from the ocean floor is known as deep-sea mining. Deep-sea mining, in contrast to conventional mining methods, collects nodules, crusts, and other deposits that have built up on the ocean floor over millions of years rather than taking minerals out of the earth’s crust. Large swaths of the ocean floor are covered in regions known as polymetallic nodules, where these deposits are frequently found. To bring the metals from these nodules to the surface for processing will take significant capital expenditure and specialized technical equipment.

Since there is currently little research on the potential long-term effects of deep-sea mining, several governments, including France, Germany, and Chile, as well as NGOs like Greenpeace, have called for a global moratorium on the practice. The lack of sufficient scientific research prompted the ISA to develop standards and guidelines for deep-sea mining gradually. The body must evaluate applications for deep-sea mining using whatever laws are in effect at the time the application is received, however, due to current ISA provisions. The ISA also mandates that prospective mining contractors obtain sponsorship from an ISA member, but with only three months left to develop regulations, it is unlikely that the pro-mortgage members of the ISA will have their concerns allayed.

The potential geopolitical effects of deep-sea mining add to the worries about its effects on the environment. The industry is dominated by a small number of states that have the resources, tools, and technical know-how needed for seabed mining due to the regulatory framework’s glacial pace. Deep-sea mining industry concentration in a small number of nations could exacerbate geopolitical conflicts already in place, particularly where competing claims to maritime boundaries and resource rights are concerned. Currently, Canada, China, Japan, South Korea, and Russia are the most important players in the market, with Norway emerging as a significant investor.

Keep Reading

For instance, tensions have arisen with rival claimants like Vietnam and the Philippines as a result of China’s imposing presence in the South China Sea. Similar to this, concerns have been raised about how Russia’s interest in the Arctic Ocean and involvement in the industry may encourage Moscow to seize control of the region’s resources in the absence of international standards and resolutions. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), which is situated in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii, is another region of particular concern. The CCZ is the most desirable and competitive region for deep-sea mining due to its estimated 21 billion tonnes of nodules, with countries like Russia, China, and the US vying for control of the zone.

Deep-sea mining expansion will undoubtedly affect the strategy and decision-making of these nations’ naval forces. Deep-sea mining presents the US with a chance to increase the resilience of its domestic supply chain while reducing reliance on imports of vital minerals. Deep-sea mining fits in well with China’s “Made in China 2025” strategy, which places an emphasis on homegrown innovation in highly specialized and technical fields and expects Chinese companies operating in the area to make the majority of the economic decisions.

Links between supply chain requirements and national security concerns have prompted both state-owned businesses and private defense contractors to assess investment opportunities in the deep-sea mining sector. However, the industry has already seen some early exits due to the prohibitive level of overhead required for operations and the dubious regulatory framework. A Norwegian startup purchased Lockheed Martin’s seabed mining subsidiary last month for an undisclosed sum and with little explanation. The subsidiary holds several exploration contracts in the CCZ.

Deep-sea mining is likely to increase the geopolitical relevance of island nations, the majority of which have historically operated in the periphery of international politics, when one looks beyond its effects on great power competition. Smaller ISA members are divided on the issue of deep-sea mining; nations like Papua New Guinea and Nauru have expressed a desire to use their mineral wealth more quickly, despite the support of their neighbors’ governments for a moratorium. In the absence of international standards before July, island nations may suffer from weakened standards that make their governments more susceptible to external pressures and influence from strong nation-states and multinational mining corporations that are planning to begin operations in the upcoming years.

Geopolitical conflicts over current issues like territorial boundaries, resource rights, and environmental regulation are likely to develop as deep-sea mining becomes more common. The ISA will have to deal with an accelerated schedule to develop a deep-sea mining code. This is despite the ISA’s reputation for the consensus-based rule. The ISA’s most important test to date will be whether it can reach a compromise before the deadline in July, with important geopolitical ramifications at stake.