Mining History: Ancient Americas

The forty-niners’ migration to California in search of gold (which gave San Francisco’s NFL team its name) is where most people think mining in the Americas began. They might also recall the 1898 Klondike rush, immortalized in Jack London’s fiction, Robert Service’s poetry, Pierre Berton’s popular history, and Charlie Chaplin’s film. Some may go back to the 16th-century Spanish precious metal mines in Central America. Mining in the Americas began thousands of years ago as a cultural and economic activity of Indigenous People.

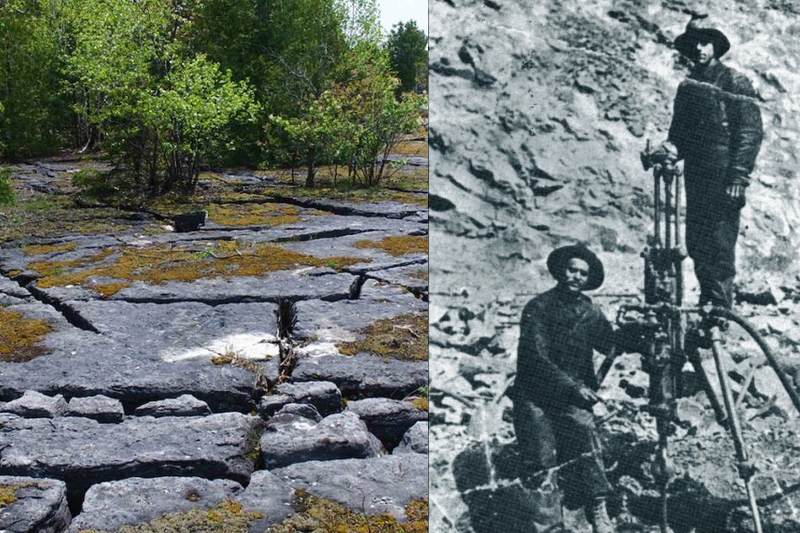

Mining is not a new theory in the Americas

Mining in this continent is very old. Manitoulin Island’s quartzite quarry is Canada’s oldest mine, dating back 10,000 years. The Maritime Archaic cultures of Labrador quarried silica-based chert and developed regional trade networks for this valuable tool-making material. As early as 6,000 years ago, indigenous people in Lake Superior stripped overburden, dug trenches and tunnels, and heated native (mostly pure) copper to make practical and ceremonial objects. Indigenous miners developed vast copper trade networks as craft workers in distant cultural groups like the Mississippi Valley mound-building cultures (800 to 1600 CE) learned to mold copper sheets over wooden carvings to create stunningly intricate artwork. Indigenous people in Central and South America mined copper and gold at least 4,000 years ago, and the Moche culture invented sophisticated smelting techniques 2,000 years ago.

Keep Reading

Many Indigenous mining and copper cultures changed in response to disease during early European contact (the agricultural Mississippians became bison hunters on the Great Plains, for example), but others survived into the modern era. The Ahtna People of Alaska controlled the vast copper deposits of the Chitina River basin until a smallpox outbreak in 1900 forced them to leave. The Kugluktukmiut (Copper Eskimos) of Coronation Gulf and the Yellowknives Dene (Copper Indians) of Great Slave Lake made copper tools and weapons into the early 20th century.

Many 19th-century geologists, anthropologists, and popular writers ignored Indigenous miners’ achievements. Some suggested that the “primitive” woodland people of Lake Superior could not have built the nearly 5,000 small copper mines in the Keweenaw Peninsula, but they mostly argued (erroneously) that an Indigenous group, likely the Mississippians, must have built them. Others went further, denying Indigenous People any role in the ancient mining of the Americas and concocting fantastic theories that placed ancient Europeans, perhaps Egyptians, Cypriots, or Minoans at the center of the story.

Recent archaeological research has proven Indigenous miners were resource development and technology innovators. Many Indigenous groups kept close ties to mining after contact, sharing information about valuable deposits with outside prospectors, providing early-stage exploration camps with local food, cutting seismic lines and wood for heating fuel, and entering the mining workforce when opportunities presented themselves. Indigenous communities in Canada have increased the power to negotiate terms of mining development in recent decades (through land claims, constitutional rights, impact and benefit agreements (IBAs), etc.). This has sped up the process.

Indigenous communities oppose mining projects that endanger local people and the land because of the historical link between colonial mining and the dispossession of traditional lands. Development proposals on Indigenous lands in northern Canada, where so much mining occurs, will be weighed against other community priorities, including Indigenous-led conservation projects that have protected large areas of land. However, many Indigenous people and communities identify as miners—drillers, heavy equipment operators, managers, or investors.

It is risky to compare ancient and modern mining practices too directly because they are so different. However, for many Indigenous cultures, their relationship with mining is based on experiences that go back to the beginning of this continent.