The Asian rise in the Middle-East

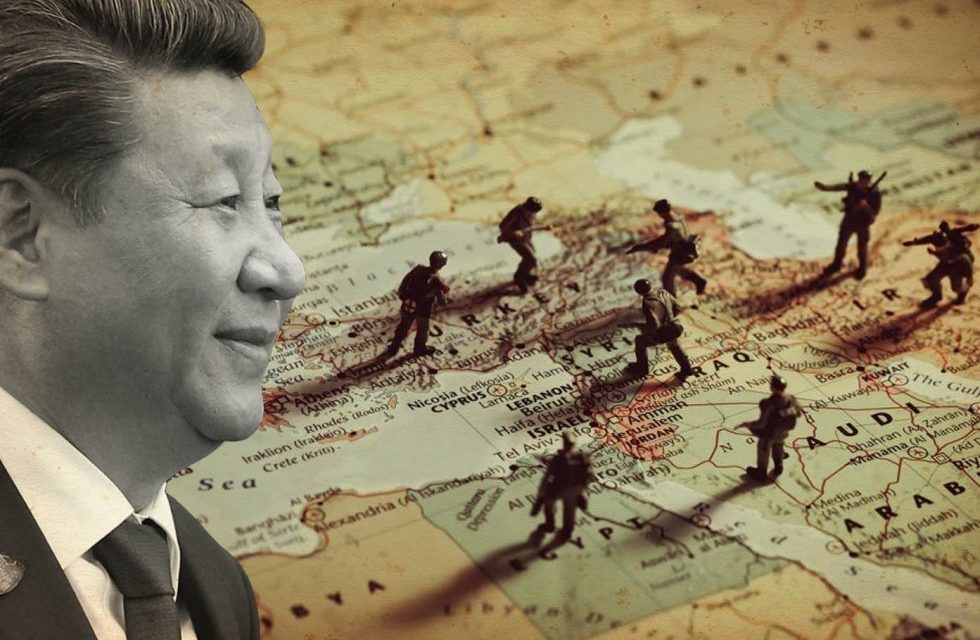

The Asian rise in the Middle-East: The presence of China in the Middle East, as an economic power and a political entity, is a growing phenomenon that is becoming increasingly evident. Mainly since the second half of the 1990s, the Beijing government has initiated a policy of penetrating the region and, at the same time, consolidated its positions in large areas of Africa. Here China has a tradition of political and economic presence dating back to decolonization, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Cold War, pursuing economic goals and satisfying its needs for raw materials and oil.

The operation also plays a purely political-strategic role, drawing inspiration from a design with global features for the concrete affirmation of China as a world superpower. But if this presence in Africa is nothing new, for the Middle-East, it is a factor with little historical precedent of importance. And it is a source of apprehension on the part of Western governments and economic interests. Traditionally, the Middle East and the Mediterranean basin have never been the focal points of China’s international strategy. During the centuries-old trade relations between the Mediterranean civilizations and the Celestial Empire, it was above all the representatives of the first to venture east – along the Silk Road like Marco Polo – rather than the Chinese merchants who made the opposite journey. Today there are many reasons why China has become aware of the importance of the Middle East. Economic growth and industrial expansion have led the Asian giant to an ever-greater need for oil.

China has been a key player in the development of human society for millennia. However, it has always maintained a position of almost voluntary isolation until the middle of the 19th century. Napoleon’s prediction remained famous: “When China wakes up, the world will tremble.” With these words, the emperor of the French indicated two characteristic elements of the Celestial Empire: the potential and future economic-political expansion of the country and the status of closure and isolation of the country at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

But this expansion today does not regard only China today. As the world economic and political center of gravity moves increasingly towards East and South Asia, we are witnessing several countries in these regions to devote more attention to the Middle East. The relations between East and South Asia and the Middle East have significantly increased as a result of the global emergence of Asian economic powers, particularly India, Japan, and South Korea. Not only oil but also business, investment, infrastructure, and tourism are the pillars of the Asian rise in the MENA region, arising questions in the West about the potential geopolitical dimension of these evolving relations.

According to Adel Abdel Ghafar, a fellow in the Foreign Policy program at Brookings and at the Brookings Doha Center, Japan’s posture towards the MENA region can be split into four different phases, starting from the 1960s. Through the decades, Japan’s MENA policy has continued to hinge upon the need to secure access to the Gulf region’s energy resources. The country continues to import about 90% of its oil from the Middle East. Less than 20% of its natural gas comes from MENA countries. During the 1980s, however, Tokyo’s diplomatic posture towards the region gradually moved closer to the policy preferences of its US ally, distancing itself from post-revolutionary Iran and strengthening ties with Israel.

Over time, and as Japan was increasingly concerned with China’s rise in East Asia, its MENA policy became a means to enhance Japan-US relations. Finally, with the era of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Japan appears willing to play a more assertive role on the world stage. Abe’s frequent visits to the Gulf region have bolstered ties with the UAE and Saudi Arabia. But Japan has been able to carefully balance these ties by implicitly backing the Iran nuclear deal and the de-escalation of regional tensions in the Gulf. Like Japan, South Korea has been dependent on oil from the Gulf region since the end of World War II. Over the past two decades, both the international and the regional scenarios have fitted into South Korea’s foreign policy vision and strategy of “middle-power diplomacy” that has been prominent in its diplomatic narrative. As Seoul strives to balance out the interests of MENA players, its posture towards the region remains one of steady and sustainable economic collaboration.

In contrast to China, the U.S. launched the Asia-Pacific Rebalancing strategy after the Iraq war, shifting its strategic focus from the Middle East to the Asia-Pacific. And from counter-terrorism to responding to the challenge of super-powers. As a result, the White House is continuing to reduce its energy dependence on the Middle East, and its strategic retreat seems to be turning into a trend. These apparent changes in the behaviour of China and the United States have spurred Iran, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and other countries to launch their versions of the Look East Policy. Recently, the Trump administration has removed Patriot missiles from Saudi Arabia and claimed it is considering reducing military personnel in Iraq. Policy changes by China, the United States, and the Middle Eastern countries seem to be sending a signal to the world, Beijing’s investment in the Middle East has profound geopolitical implications and has even passed Washington.